Overview

When the Army Air Corps found itself short on weather forecasters at the outset of WWII, it teamed up with academia to increase training of weather officers. MIT was the first of three American universities to offer graduate degrees in meteorology at the time and contributed to the training of African-American military pilots popularly known as the Tuskegee Airmen. In the summer of 1940, the Institute began offering abbreviated courses in the teaching of meteorology to select aviation cadets. Candidates requirements included: engineering or other degree, two years in mathematics (including differential equations and integral calculus), and one year in physics.

Among the MIT alums who served as Tuskegee Airmen were Wallace Patillo Reed '42, Second Lieutenant Victor L. Ransom '48, aeronautical engineers Yenwith Whitney '49 and Louis M. Young '50, and meteorologist Charles E. Anderson PhD '60.

Tuskegee Institute

A 1920s War Department report stated that blacks weren't intelligent or disciplined enough to fly a plane. During World War II, black civil rights groups tried to get the U.S. military to add black pilots to its ranks. The 66th Air Force Flying School was opened at the historically black college Tuskegee Institute (today Tuskegee University) in Alabama.

The flying school was opened as an experimental training ground to test the potential of black pilots.

"It was programmed to fail," said [Tuskegee Airman Yenwith] Whitney, noting that the school was set up as a tool to back up the findings of a 1920s War Department report stating that blacks weren't smart enough or disciplined enough to fly a plane.

Under the direction of Charles Alfred "Chief" Anderson, the pioneering airmen practiced at Moton Field, a tiny airstrip surrounded by marshes and stands of pine near the institute founded by Booker T. Washington, the son of a slave who was a strong advocate for black rights.

During their flight training, the airmen were denied rifles because the airstrip was in Alabama, a deeply segregated state where some folks didn't like the idea of blacks shooting at whites --- even if they were the enemy.

The drills became bittersweet to the airmen, whose hopes of flying dimmed as they waited and waited for a call-up from the government. After months of waiting, their spirits were restored by a visitor to the airstrip.

"I've always heard colored people can't fly, but I see them flying around here," Eleanor Roosevelt reportedly said during her visit. Against the objections of her security men, the open-minded, free-spirited first lady asked to fly with Anderson.

Using her political connections, Roosevelt convinced her husband to use his influence to give the airmen a chance to fight --- especially since the military was facing a critical shortage of pilots.

The Tuskegee Airmen not only broke the color line, they shattered stereotypes about black pilots.

George L Washington

George Leward Washington '25, MS '30 earned his Bachelors (1925) and Masters (1930), both in Mechanical Engineering (Course II). He became the first black registered engineer in the state of North Carolina. Before World War II, he helped establish an Air Force training program for black pilots at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Washington later served as the director of special services for the United Negro College Fund.

From "Training at Tuskegee: Turning dreams into reality" by Randy Roughton, Air Force News Service, 11 February 2014

[A driving force in why the Army considered when choosing Tuskegee as the training site for African-American pilots] was George L. Washington [MIT Class of 1925], an engineer and director of mechanical industries and the Tuskegee Institute Division of Aeronautics, who was instrumental in bringing the primary flight training program to Tuskegee. He oversaw the construction, outfitting and expansion of Moton Field, and as general manager, he hired and supervised flight instructors, airplane maintenance personnel, and other support personnel, and ensured that cadets were properly housed and fed. While the Army looked at the training of African American pilots as an experiment, Washington didn’t see it that way.

“Acceptance of Negroes into the Air Corps for training as military pilots meant one thing for the Negro and another to the military establishment, and possibly white Americans,” Washington wrote in his unpublished papers that are kept in the Tuskegee University Archives. “For the Negro, it was an opportunity to further demonstrate his ability to measure arms with any other race, particularly white Americans, when given an equal opportunity. Performance in civilian aviation had certainly proven their ability to fly as individuals. And certainly this had to be the prime requisite for success in military aviation. Therefore, this was just another in the long chain of demonstrations over many years. Certainly this opportunity was far from being an experiment to the Negro.”

Image: Courtesy MIT Museum

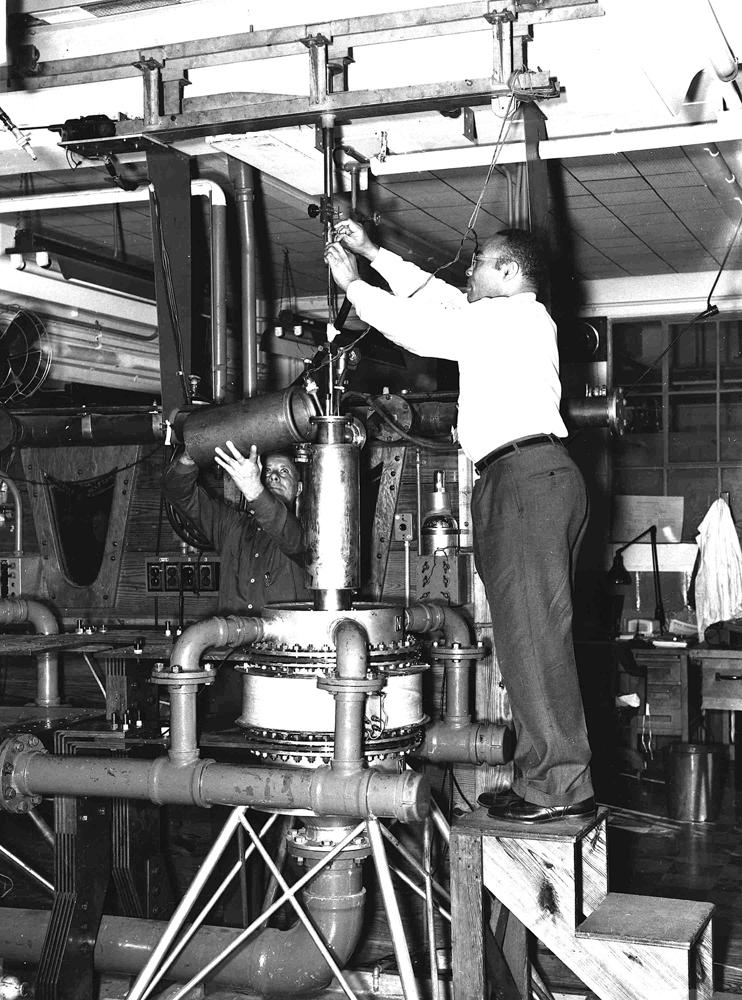

Warren Henry

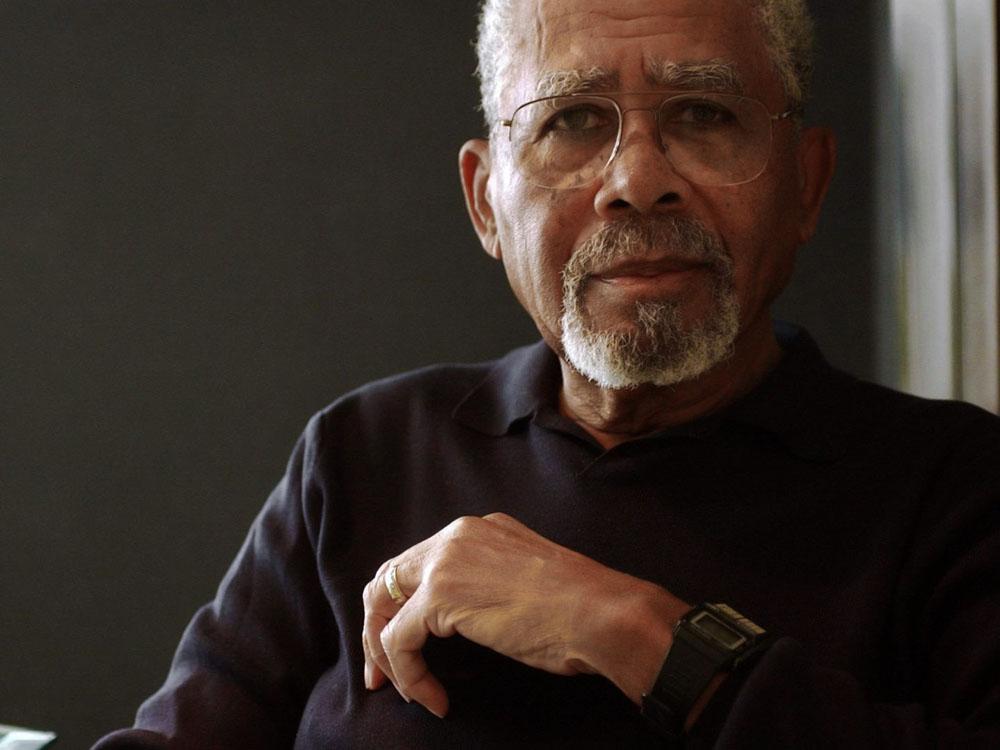

Chemist-physicist Warren Elliott Henry was born to two Tuskegee alums who were local schoolteachers. He grew up on a peanut farm in Alabama, where George Washington Carver often conducted research on crops.

Henry earned a Bachelor of Science (1931) from Tuskegee Institute, a Master of Science in Organic Chemistry (1937) from Atlanta University, and a PhD in Physical Chemistry (1941) from the University of Chicago. He returned as faculty to Tuskegee Institute in 1941, before being recruited by the MIT Radiation Laboratory in 1943.

Pioneering NRL Physicist had Tuskegee Ties

U.S. Naval Research Laboratory News Release (23 February 2012)

Training Tuskegee Airmen

Returning to Tuskegee [in 1941], Henry took a position as an assistant professor of chemistry. Because of his broad program of studies at Chicago the Institute qualified him to teach physics, asking him to teach special physics courses to the young men who were training to be Army Air Corps officers. These young men ultimately formed the 99th Pursuit Squadron and became world famous as the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II.

MIT Radiation Laboratory

During the war and a break from teaching, Henry visited fellow University of Chicago alumni, Persa Raymond Bell at the [MIT] Radiation Laboratory. Bell had shown Henry the type of research being conducted to contribute to the war effort, and asked if he would like to work there. Shortly after, Henry was recruited by MIT in 1943 to undertake a crucial project for the U.S. Navy.

Classified as top-secret, Henry worked to develop video amplifiers that were used in portable radar systems on warships. The amplifiers, capable of detecting and tracking targets like German submarines, filtered and strengthened radar signals and were considered 'faster than anything else at the time.'

After Tuskegee and MIT

Henry later held positions at University of Chicago, Morehouse College, Howard University, the Naval Research Laboratory, and Lockheed Missile and Space Company. He was a Fellow of the American Physical Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Source: U.S. Naval Research Laboratory

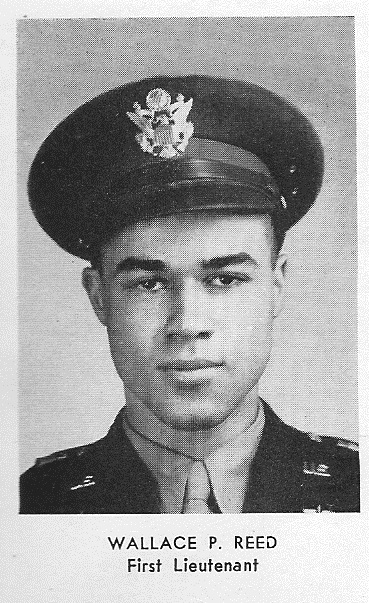

Wallace Patillo Reed

Valentine’s day marks 1st for African American Meteorologist

Nellis Air Force Base News (21 February 2012)

by Jerry White, 99th Air Base Wing Historian

On Feb. 14, 1942, the first African-American meteorologist in the armed services graduated from a specialized training course at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Wallace Patillo Reed was found through an extensive search by MIT officials at the request of the Army Air Forces [AAF]. In 1940, the Army had only 62 qualified weather forecasters. With WWII expansion already underway, it was initially estimated that as many as 10,000 weather officers were needed just for the AAF; by war's end, more than 6,000 had been trained.

Cadet programs were set up initially at MIT, New York University and the California Institute of Technology, with additional courses later at the University of Chicago, the University of California Los Angeles and an AAF program at Grand Rapids, MI. Potential weather officers needed engineering, math, physics or chemistry degrees, later lowered to at least two years of coursework. Reed entered MIT's second class in 1941, followed by 14 other African-American aviation cadets and one enlisted forecaster before the program closed in 1944.

Upon graduation, Reed was commissioned into the Army Air Corps, three weeks before the first class of pilots graduated from pilot training at Tuskegee Army Air Field, Ala. After a three-week orientation at Mitchel Field, New York, Lt. Reed was assigned as the Tuskegee AAF base weather officer.

Reed served his entire tour in charge of the base weather station there and helped train weather officers who deployed overseas. After the war, he moved to the Philippines where he worked for Pan American Airways and the Weather Bureau. Years later he returned to the United States, passing away in 1999.

In addition to being the first African-American meteorologist in the military, Capt. Reed is believed to have been the Weather Bureau's first African-American meteorologist.

After Tuskegee

In 1946, after serving in World War II, Reed took a post as a government official, connected with the U.S. Weather Bureau at Nickols Field. He lived in Manila for over three decades before moving back to the United States.

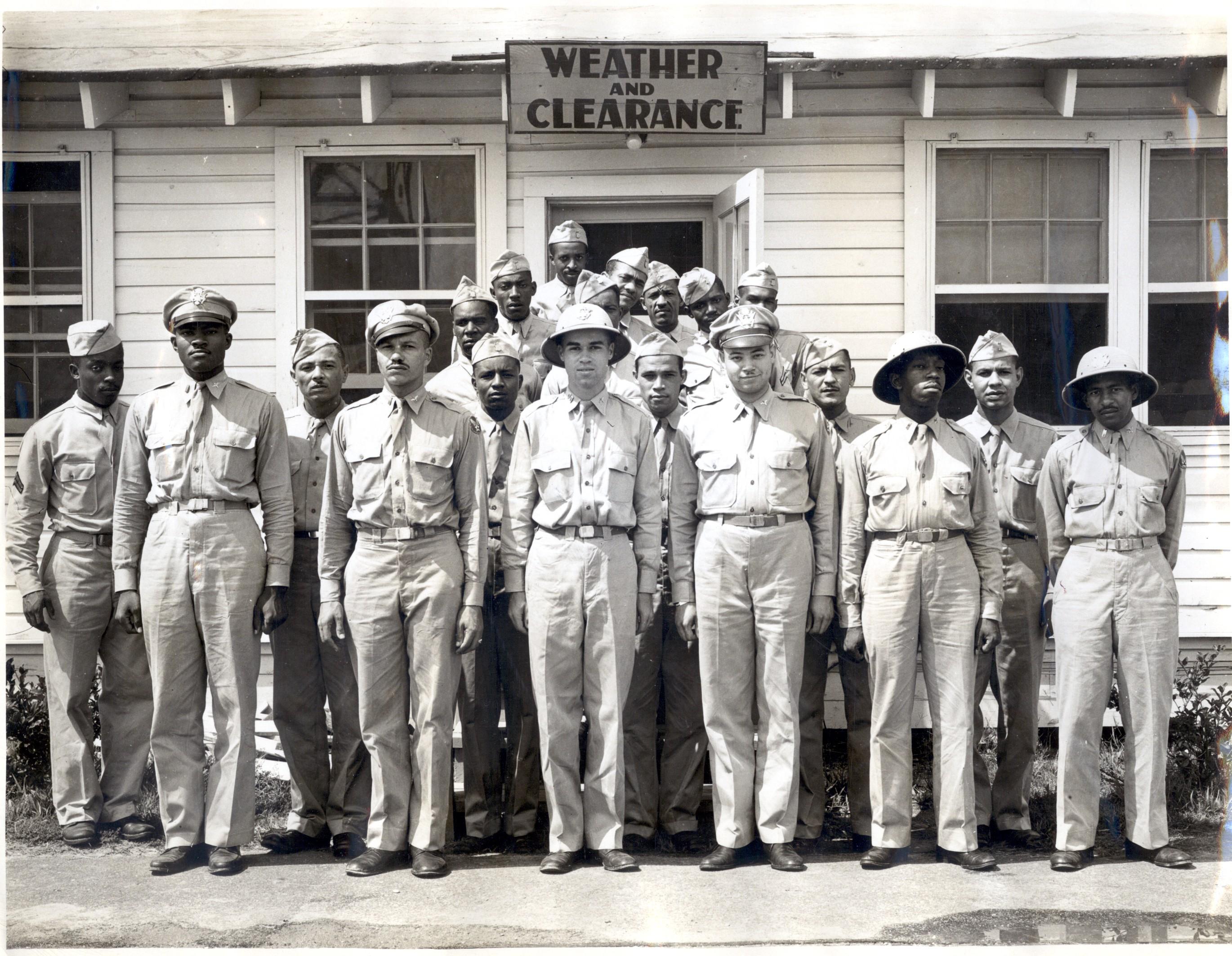

Personnel of the Tuskegee weather detachment, which served with both the 332nd Fighter Group and 477th Bomb. circa 1944. Pictured (front row, left to right): Lt. Grant Franklin, Lt. Archie Williams, Capt. Wallace Reed, Lt. John Branche, Lt. Paul Wise and Lt. Robert Preer.

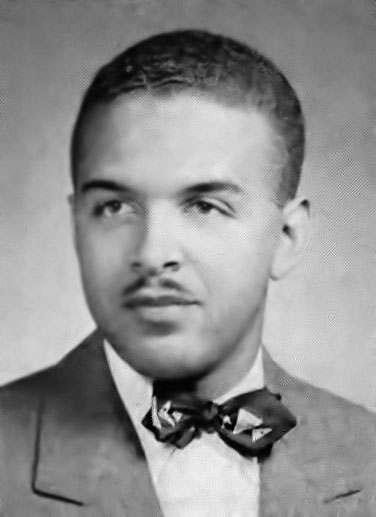

Victor Ransom

Background

Victor "Vic" Llewellyn Ransom '42 was born in New York City to a schoolteacher and a writer, both of whom were part of the Harlem Renaissance. Chasing after top schools for Ransom, the family moved 16 times before he turned 16. He graduated from Stuyvesant High School, a magnet public school known for its rigorous math and science curriculum. By senior year, Ransom had already set his sights on studying electrical engineering at MIT.

At the Institute

Ransom's memories of his arrival to the Institute in 1941 are vivid. His impression of the campus was of a "War Department," with "massive, unsympathetic buildings". In December of that year, in fact, events at Pearl Harbor led to the United States' entry into World War II. During his sophomore year at MIT, Ransom took a leave from MIT for service training.

I received a letter from the ROTC program, which I was involved in, that said something like, "This man has had training in engineering and ought to be considered for the Signal Corps." Well, the Army had no idea what to do with that note like this about a black soldier, so I stayed in the reception center for a couple of months while they tried to figure it out.

Victor Ransom in Technology in the Dream by Clarence G. Williams (MIT Press, 2001)

Second Lieutenant Victor L. Ransom '48, who was among the 101 Tuskegee Airmen who took part in the 1945 Freeman Field Mutiny protest against segregation, shown ca. 1942.

Freeman Field Mutiny

Black officers at Freeman Field, Indiana were segregated in an abandoned cadet field and referred to as "trainees," regardless of rank. A member of the the 477th Bombardment Group, Ransom was among the 101 Tuskegee Airmen who took part in the Freeman Field Mutiny protest against segregation in 1945.

The war ended without Victor Ransom ever leaving U.S. soil. But he and other members of the 477th Bombardment Group were busy fighting a different battle.

Activated in June 1944, the 477th was plagued by delays and inefficiencies, due in large part to its commander, a white colonel and rigid segregationist who moved the group from base to base 38 times in less than a year to try to quell dissent. Fed up, a group of black officers staged a quiet, nonviolent protest at Freeman Field, Indiana, on April 5, 1945, when they tried to enter a club used by white officers only...

“I was the first guy into the [white] officers’ club,” says Ransom...“They said to go back to quarters and remain there. So we were under arrest in quarters for violating an order.”

Cleared by a congressional inquiry, Ransom and the others were released within a few weeks. A few months later, the war ended and Ransom returned to MIT to complete his graduate work in electrical engineering...

“My achievement was our efforts to integrate the officers’ club,” he says wryly. “It was silly. But it characterizes the nature of the country at the time.”

"Double Victory: Jersey’s Tuskegee Airmen" by Mary Ann McGann, New Jersey Monthly, 18 January 2013

Post-war and MIT

After the war Ransom resumed undergraduate studies at the Institute, completing his remaining years under the GI Bill in 1948. Though faced with a tough job market after MIT, Ransom received an immediate job offer from NACA--precursor to NASA--at the Langley Field Lab in Hampton, Virginia. Segregation led him to transfer to NACA's Lewis Lab in Cleveland, Ohio, where he would be able to complete graduate studies; in 1957, Ransom earned his Masters degree in Electrical Engineering from Case Institute of Technology (today Case Western).

Ransom joined Bell Laboratories, moving up the ranks at Bell Labs and in the communications industry for the next 30 years. His areas of specialty included transistors and digital products, network switching technologies, systems for special needs, and environmental control systems design.

Yenwith Whitney

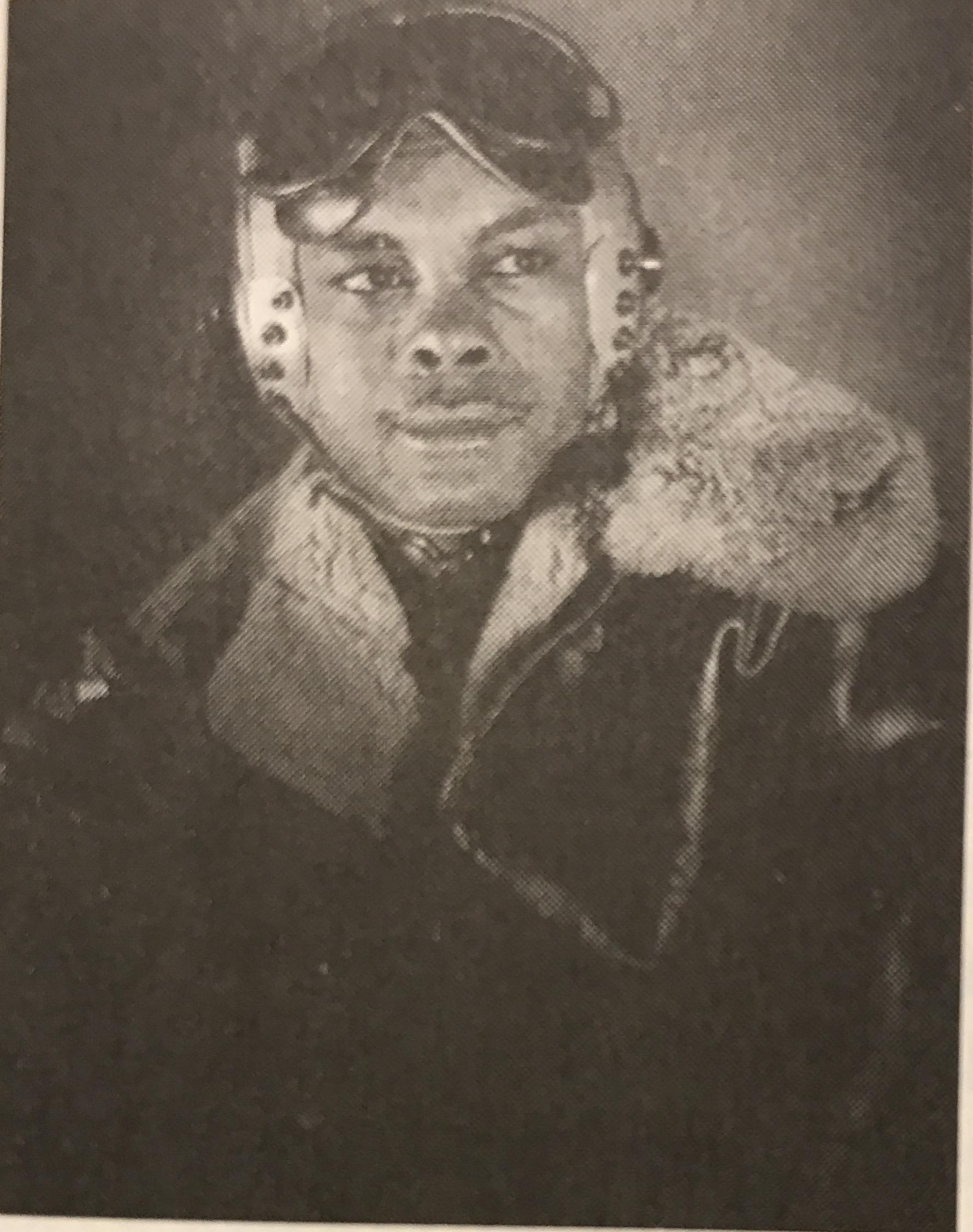

Yenwith K. Whitney '49 enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps in 1943. He was an 18-year-old Bronx native who had grown up attending a predominantly white school and local church. After graduating high school during World War II, he signed up for the fledgling black aviation program.

My first real experience with black kids was living in the army air corps...It was my first profound exposure to being part of a group that was exclusively black.

Yenwith Whitney to MIT Technology Review, 1 November 2003

Many commanders didn’t want blacks doing anything but menial labor in World War II. They didn’t think blacks were smart enough to do things like fly airplanes...I took my basic training in Biloxi, Miss. I had never been in the South before and it didn’t make me very happy to be in Biloxi. They told us before we went South, we only had one purpose being there and that was to train. Don’t get in any kinda trouble.

Yenwith Whitney at a North Port Library Black History Month lecture,Charlotte Sun, 20 February 2003

From Biloxi, Whitney went on to train at the Tuskegee Institute's 66th Air Force Flying School at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

There was only one thing we dreamed of and that was getting our wings. If you washed out, it was the most devastating thing that could happen to you...We started out with 64 in our class, but only 26 got their wings and graduated. That was the greatest day of my life. I had achieved something significant.

Yenwith Whitney in a North Port Library Black History Month lecture,Charlotte Sun, 20 February 2003

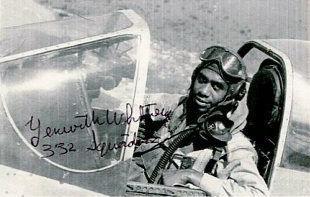

In 1944, he went on to serve as a pilot in one of four all-black fighter units in the 332 Fighter Group (“Red Tails”), assigned to the all-black 301st Fighter Squadron, of the 15th Air Force. During the war, Whitney flew 34 combat missions in Europe as a fighter pilot escorting heavy bombers, earning an Air Medal and three Clusters for his service.

Autographed 3x5 postcard depicting Tuskegee Airman Yenwith Whitney of the 332 Fighter Group (“Red Tails”), assigned to the all-black 301st Fighter Squadron, of the 15th Air Force, ca. 1944.

Post-War

Despite earning an Air Medal and three Clusters for his service, Whitney was unable to get a job with a commercial airline after the war.

I was angry. I was just as qualified as anyone else. I enrolled in the best school I could think of.

Yenwith Whitney in the Bradenton Herald, 18 April 2011

He applied to MIT under the GI Bill and was accepted. In 1949, Whitney earned a Bachelors in Aeronautics and Astronautics (Course XVI) from MIT in 1949.

After earning his degree from MIT, Whitney worked for Republic Aircraft on stress analysis, then for the EDO Corporation on structural design of aircraft floats. In 1958, he and his family moved to Cameroon, where Whitney taught math and physics at a Presbyterian mission. The family returned to New York a decade later, although Whitney continued working for the United Presbyterian Church in minority education and international education in Africa, the U.S., and Asia. Whitney also earned a Master’s degree in math education and a doctorate in International Education from Columbia University.

After his retirement in 1992, Whitney became active with the MIT Alumni Association, where he was involved on their national selection committee. He served on the board of directors of the MIT Club of Southwest Florida, as an educational counselor, and as president of Black Alumni/ae of MIT (BAMIT).

“When I went to MIT, I was well treated and had a good experience in the dormitory, the fraternity, and in intramural sports,” he told MIT Technology Review. “Yet there were only three other black students when I was at MIT, which is why I became so interested in BAMIT. I think BAMIT is a very important part of MIT and extremely important for black students.”

Watkins, William, et al. Yenwith Kelly Whitney Collection. 1943. Personal Narrative. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.72551/>.

Louis Young

Louis M. Young '50 was born in Detroit, Michigan, where he developed a love of airplanes. He built model airplanes and dreamed of becoming an aeronautical engineer or pilot.

After leaving the Army in 1946, Young attended Wayne State University for only a week. He quit after being told that all he "could ever do was to be a mechanic in that day". He worked at a hotel, then at a factory, before going into the military. After doing basic training, he went to Tuskegee.

At Tuskegee

I was one of the original Tuskegee Airmen...When I got to Tuskegee, I immediately got shipped up to navigation, being a navigator. They didn't have many people who were mathematical there. Here we were in a sort of segregated deal. We'd go in to breakfast at 7:00 AM, and an hour later the white students were by themselves and they ate. They kept us completely separate...In order to get a haircut, I had to go sixty miles from Hondo, Texas to San Antonio.

At the barracks...they put the white boys to bed first. After they go to sleep, they bring us in and in the morning they took us out...Then later in the war, there were a lot of guys coming back from overseas. We heard about what they had done over there…

We got [to the Oklahoma station] and the guy who was doing overseeing, when you walked into those barracks they made sure that we were treated right. We had separate toilets and all that sort of stuff, but we got pretty nice treatment. The thing that was bad there was you could do the least little thing wrong and they would kick you out...just looking at somebody wrong or just saying the least little thing. You had to be awfully sensitive in interacting in that place, and that's how you did the white folks. You figure out what they're trying to get you to do and you find ways to keep doing it, doing it better...You had to learn how to play [the part] quietly and not angrily or in a personal way...You had to be a person who could stay cool under pressure..."What can I do to take this pressure and reverse it the other way?" That's what I tried to do and I did it.

Louis Young in Technology and the Dream, 1997

Courtesy Louis M. Young

At the Institute

I got out of the military in '46, and when I left there went directly to MIT...the military paid my way. At that time, it cost eighty-five dollars a year to go to MIT. What they told you when you first got into the Institute--you get in that big hall where everybody sits together--"Look at the person on your right. Next year two of you won't be here"...I was really the only black [student at MIT] my year for four years.

I was the only guy in the aeronautical engineering class ['50] to get a job in 1950 for six months. I got mine immediately. But at my proudest moment, when I had this gal with me that I was going to get married to, we were standing in the elevator before graduation and this white guy got on and said, “How come this goddamn nigger can get a job and I can’t?” I learned that not only was I the only black in the aeronautical force, but none of the other students got a job until six months after I did...I was not the first black at Lockheed. I was the second one hired.

Louis Young in Technology and the Dream, 1997

After MIT

After earning a Bachelor's in Aeronautical Engineering from MIT in 1950, Young became a Senior Design Specialist at Lockheed-California Corporation. He was the first African-American to work for Lockheed's engineering department. He served for 38 years and, after numerous promotions, retired in 1989 as Chairman of the Board, Planning. By 1997, Young was serving as President of the Tuskegee Airmen Scholarship Fund Program.

Luther Prince Jr

Luther T. Prince, Jr. '52, MS '52 was born to a railroad brakeman and a homemaker in Fort Worth, TX. In 1943, he enrolled at the Tuskegee Institute, mistakenly believing it to be directly affiliated with the all-black Army Air Force 99th Pursuit Squadron, which trained the Tuskegee Airmen. Prince transferred to Ohio State University a year later, but World War II interrupted his studies in 1946. He served three years in the Army before applying to MIT. In 1952, Prince earned both his Bachelors and Masters degrees in Electrical Engineering.

He was hired a year later by the electronics company Honeywell. At the Minneapolis headquarters he designed flight-control systems for aircrafts and missiles, rising to engineering supervisor after eight years. In 1967, Prince became CEO of the ailing Ault, Inc., an electrical components maker in Minneapolis. Prince's development of a standardized plug-in wall unit increased the company's growth and paved the way for minority business in the private technology sector. Prince was the first African American to be inducted into the Minnesota Business Hall of Fame.

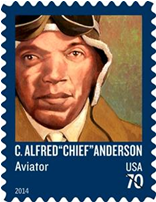

Charles Anderson

Charles "Chief" Alfred Anderson PhD '60 was the first African American to hold a PhD in meteorology, which he earned from MIT in 1960. In 2007, he was awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor.

From "Training at Tuskegee: Turning dreams into reality" by Randy Roughton, Air Force News Service, 11 February 2014

Airport 1 would be Kennedy Field, which was no more than a sod runway with a few buildings for aircraft and refueling equipment. Kennedy became most known for Charles A. (“Chief”) Anderson’s famous flight with first lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1941. But the program’s chief instructor meant much more to the many Tuskegee Airmen he trained.

Tuskegee Institute recruited him in 1940 to be the chief civilian flight instructor for African American pilots. Anderson developed a pilot training program and taught the first advanced course, and in June 1941, the Army named him the ground commander and chief instructor for cadets in the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the nation’s first African American fighter squadron.

To many Tuskegee Airmen, Anderson, who died in Tuskegee in 1996, will not only always be “Chief.” For them, he was also “the beginning” of their journey into military flight.

“Chief pilot wasn’t just a position in the staff we were operating,” said Roscoe Draper, who joined Anderson as an instructor in 1942. “It was also an honorary position in our hierarchy. He was considered the coach of the pilots.

“I will always feel I owe him an awful lot, the way he opened doors for me. Chief Anderson opened doors we never could have approached otherwise.”

"Charles E. Anderson '48 Awarded Congressional Medal of Honor," NYU-Poly eBriefs, a publication of the Polytechnic Institute of New York University, 30 March 2007

Sixty-two years after their legendary World War II exploits, the members of America's first all-black fighter squadron, the Tuskegee Airmen, were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor on March 29, 2007. In 1940, at a time when Blacks were barred from serving in the U.S. Military flight training program, Charles Edward "Chief" Anderson, who would later become a 1948 alum of the polymer chemistry program at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, started the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) at the Tuskegee Institute of Alabama.

Anderson's CPTP and its military follow-on, which he also directed, were responsible for training the pilots who became the famous Tuskegee Airmen. "Chief" Anderson is widely acclaimed as the father of Black Aviation. A self-taught pilot, Anderson was the first African American to receive a pilot's license in 1929.

Renowned for their squadron's achievements, the Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 sorties over North Africa and Europe during World War II and destroyed more than 250 enemy aircraft on the ground and 150 in the air. The squadron never lost a bomber to enemy aircraft fire during their escort missions. No other escort unit could claim such a record. In recognition of their outstanding service to the nation, the entire squadron is now [2007] being honored as a group with the Congressional Medal of Honor.

When Eleanor Roosevelt visited Tuskegee Army Air Field in 1941, she insisted on taking a ride in an airplane with a black pilot at the controls. The First Lady's pilot was "Chief" Charles Anderson. Mrs. Roosevelt, a pioneering Civil Rights Activist, insisted her flight with Anderson be photographed, and immediately developed the film so she could take pictures back to Washington to persuade FDR to activate the Tuskegee Airmen in North Africa and in the European Theater.

Eleanor Roosevelt (center) and Charles E. Anderson (right) at Tuskegee Army Air Field, 11 April 1941. She had insisted that the flight be photographed, and immediately developed the film in order to take the photos back to Washington and persuade FDR to activate the Tuskegee Airmen in North Africa and in the European Theater of World War II.

Credited with the training of over 900 airmen at the Tuskegee Institute, Anderson's flying squadron helped persuade President Harry Truman, in 1948, to end segregation in the U.S. military, thus opening America to a new social order. That same year, Anderson received a Masters of Science in Chemistry from the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, and went on to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to become the first African American man to receive a PhD in Meteorology in 1960, with a dissertation entitled "A Study of the Pulsating Growth of Cumulus Clouds".

From 1965 to 1966 Anderson worked in Washington, D.C., as the director of the Office of Federal Coordination in Meteorology in the Environmental Science Service Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. In this position Anderson established the first World Weather Watch program.

In 1966 Anderson began a 20-year career at the University of Wisconsin when he became the University's first tenured African-American professor. At Wisconsin, Anderson was professor of space science and engineering, professor of meteorology, chairman of the Contemporary Trends course, chairman of the Afro-American Studies Department, and chairman of the Meteorology Department. In 1978 he was appointed associate dean of the University.

In 1970 Anderson participated in the Northeast Hail Research Experiment where scientists were first able to use satellite data in their research. Having earlier worked with IBM computers at Douglass Aircraft Missiles and Space Systems Division, where he built upon the work of Joanne Simpson to produce the first moist cloud model on a computer, Anderson took full advantage of the satellite data and the growing field of computer science to study storms and tornadoes.

Using remote sensing technology that had been designed for oceanography, Anderson revolutionized the field by introducing new analytical schemes and high-powered statistics, and gained national recognition for storm forecasting. In particular, Anderson discovered ways to identify tornadic storms by the way they spin, which led to scientists' ability to predict severe storms and tornadoes up to an hour before they arrived in populated areas.

As a research professor, Anderson challenged fellow faculty members to strive for high quality research and to be truly productive members of the research community. Anderson continued working until his death on October 21, 1994, from cancer. In 1999 the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) established the Charles Anderson Award to honor his contributions to meteorology. According to an NCAR news release in 2000, the award was established "to recognize individuals or organizations for outstanding contributions to the promotion of educational outreach, educational service, and diversity in the atmospheric science community."

The postal stamp issued in Charles Anderson's honor is the 15th stamp in the Postal Service’s Distinguished American Series. “The Postal Service is proud to honor Charles Alfred 'Chief' Anderson, a Black aviation pioneer who inspired, motivated and educated thousands of young people in aviation careers, including the famed Tuskegee Airmen of World War II,” said U.S. Postal Service Judicial Officer William Campbell in dedicating the stamp whose father was a decorated Tuskegee Airman who served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.